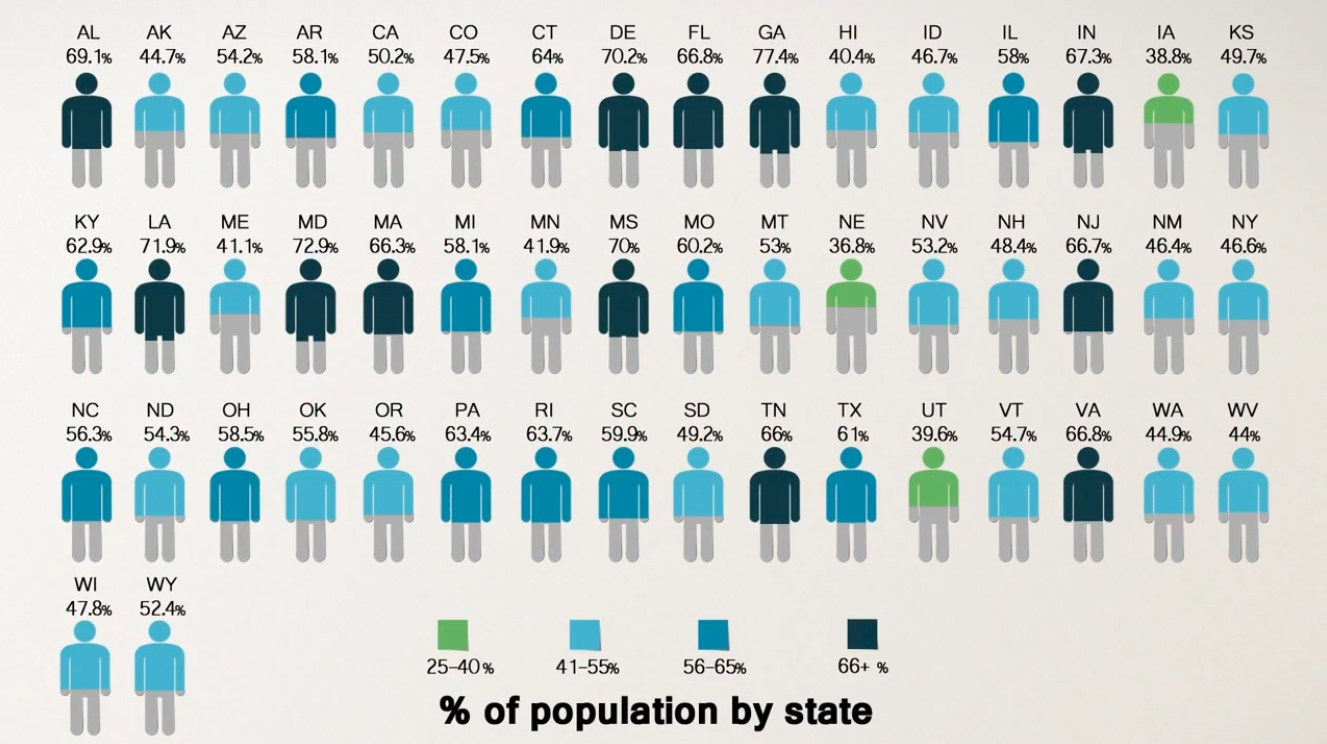

In 2014, the House Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit held a hearing to discuss a bill aimed at expanding credit access for millions of Americans. According to Representative Keith Ellison of Minnesota, there were at least 50 million consumers in the country whose credit histories were too thin to generate high scores and another 50 million who were “credit invisible,” meaning that they had no credit scores at all.235

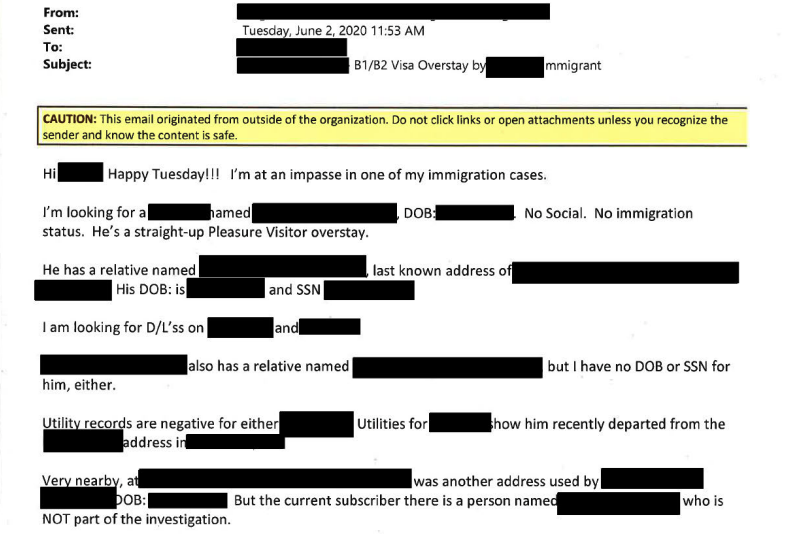

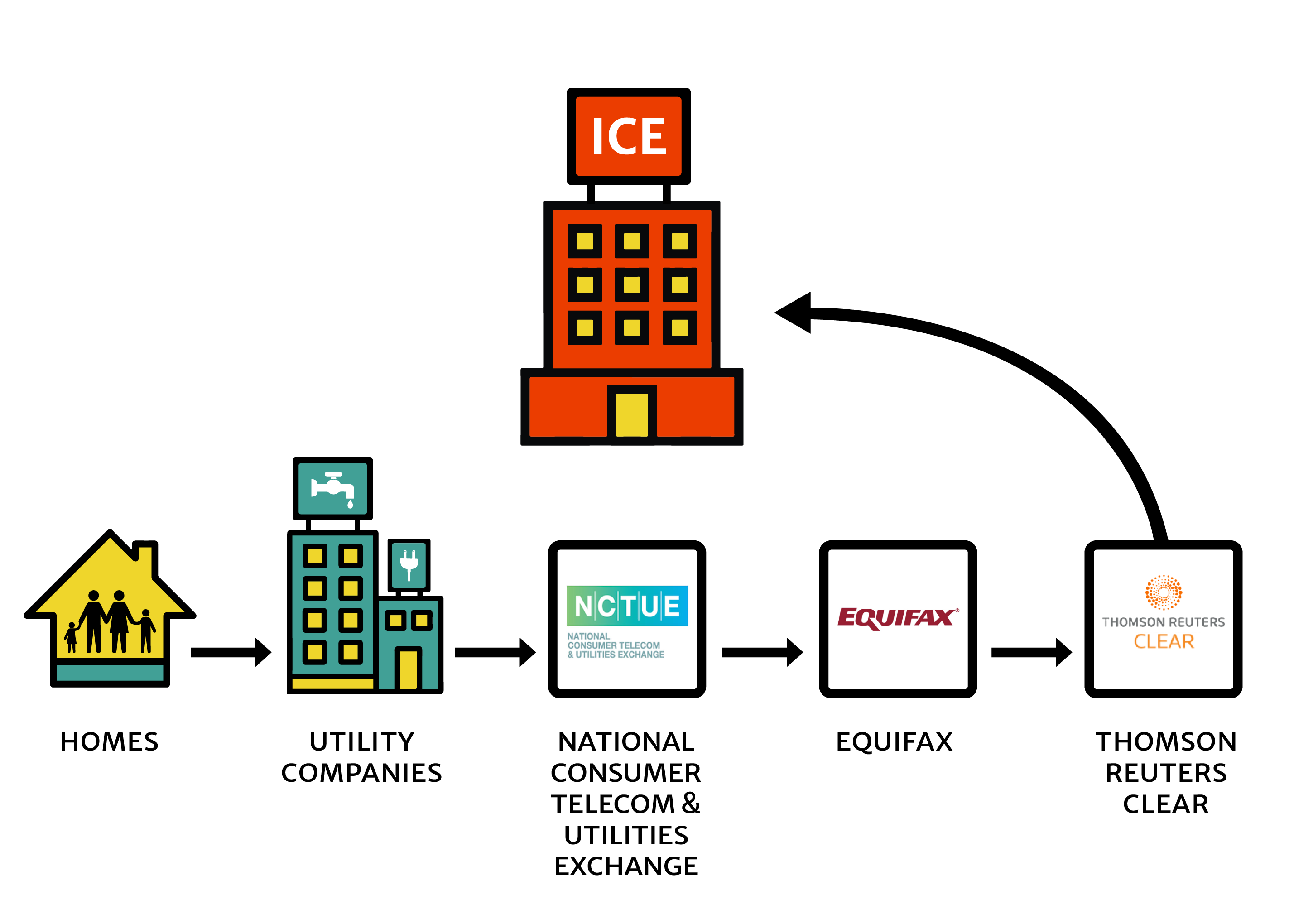

“The solution is simple,” Ellison told the committee.236 Instead of needing credit to build credit, consumers could establish a record through something that many people already pay on a regular basis: their utility bill. The Credit Access and Inclusion Act would give the green light for gas, water, electric and other utility providers to notify credit bureaus each time a customer pays—or misses—a monthly bill, not just when an account is sent to collections.237

The idea behind using utility payments to show creditworthiness wasn’t entirely new, and one major credit reporting agency, Equifax, was already collecting the “full-file” utility payment records of millions of customers for use in specialized credit reports delivered specifically to utility companies.238 But the law was still unclear on whether full utility payment data could be factored into a consumer’s credit score, and Ellison wanted to put an official rubber stamp on the practice. Approval from Congress, he hoped, would go a long way in helping low-credit and no-credit Americans break into the mainstream financial system.239

- 235. An Overview of the Credit Reporting System: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit of the House Committee on Financial Services, 113th Cong. (2014), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-113hhrg91161/html/CHRG-113hhrg91161.htm. (“More than 50 million Americans have no credit score, are just credit-invisible. Another 50 million have scores that are lower than they should be because they do not have enough lines of debt to generate a score.”).

- 236. Id.

- 237. See National Consumer Law Center, Full File Utility Credit Reporting: Harms to Low-Income Consumers (2013), https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/credit_reports/ib_utility_credit_2013.pdf (“One of the efforts to promote alternative credit data urges that utility companies engage in monthly reporting of customer payments, including late payments, to the Big Three nationwide credit reporting agencies (CRAs), Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. Currently, the vast majority of electric and natural gas utility companies only report to those three CRAs when a seriously delinquent account has been referred to a collection agency or written off as uncollectible.”).

- 238. See An Overview of the Credit Reporting System: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit of the House Committee on Financial Services, 113th Cong. 137–38 (2014), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-113hhrg91161/html/CHRG-113hhrg91161.htm (letter from Buddy Flake, NCTUE Board President, and Micheal Gardner, Senior Vice President, Equifax, to Keith Ellison, Member, Committee on Financial Services) (“[The National Consumer Telecom & Utilities Exchange] is a nationwide, member-owned and operated, FCRA-compliant data exchange that houses both positive and negative alternative payment data (i.e., non-traditional financial payment reporting data, such as telecom and utility payments) on consumers, which is then available to NCTUE’s members on a blind basis to aid in their credit decisioning and risk management...member companies currently report and share industry-specific payment data on more than 180 million consumers throughout the United States.”).

- 239. See An Overview of the Credit Reporting System: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit of the House Committee on Financial Services, 113th Cong. (2014), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-113hhrg91161/html/CHRG-113hhrg91161.htm (statement of Hon. Keith Ellison) (“I am eager to see this Congress take action to improve our [credit reporting] system by making it more inclusive. … Mr. Fitzpatrick and I, in a bipartisan way, have a bill called the Credit Access and Inclusion Act, and this bill clarifies that current law does not prohibit utility and telecom firms from reporting their customers' on-time payments.”).